We’ve come across a couple of cases this year that serve as “teachable moments.” This might be the best one yet. Certainly it was a good one for Zappos.

The premise for our Lesson of the Day is that basic contract principles require, as the Court in this case said, “an offer and acceptance, meeting of the minds, and consideration” for a contract to be enforceable. This is no different on the internet then it was when agreements were pounded out on a typewriter (remember those?)

In January of this year, Zappos had a security breach in which hundreds of its customers’ personal information was accessed by hackers. (There may be lessons for data security in there as well, but the Court didn’t get into that). Some of their customers claimed that they had been damaged by this security breach, and sued.

Zappos had an arbitration provision in its Terms of Use on its website, and filed a Motion to Compel Arbitration. There is a widely held idea that arbitration is a cheaper and more efficient model of dispute resolution. There is good reason to question that assumption these days, but there is some support to the theory that arbitration tends to favor big organizations like Zappos. The plaintiffs, evidently believing that arbitration might not go in their favor, opposed the motion, so the District Court of Nevada weighed in. And ended up throwing out Zappos’ Terms of Use completely. Zappos was left without any contract at all to govern its relationship with its customers. A scary result, but in this case, the right one.

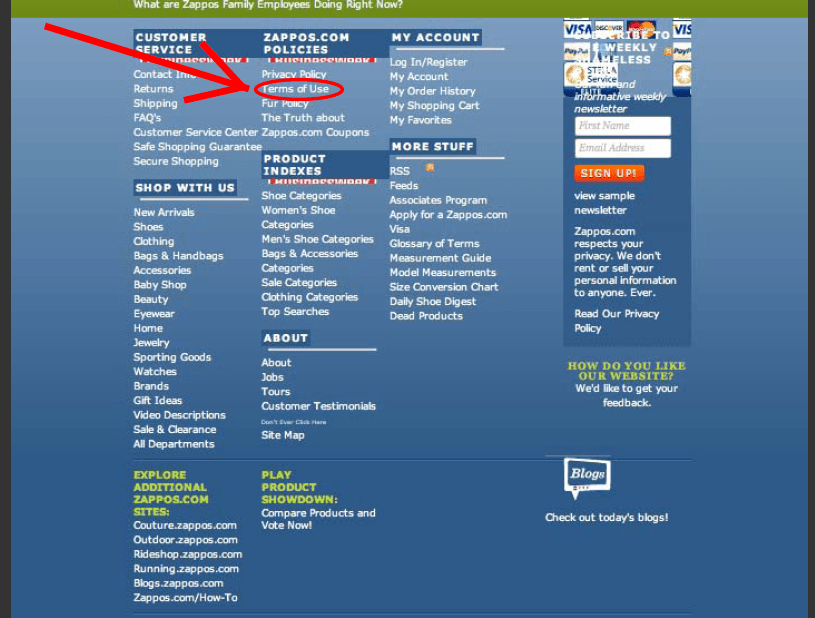

Zappos’ Terms of Use are at the very bottom of the page, buried in with a bunch of other links that no customer looking for the latest Frye Boots is ever going to read. Here’s a picture of where the Terms of Use show up on the Zappos site. It’s only a picture of the bottom of the screen (the opinion points out that when the home page is printed out, the Terms of Use show up on page of 3 of 4). Amazingly, Zappos still doesn’t seem to have fixed the problem that got them into trouble.

Terms of Use which are simply in a link on the website (and buried so far down you have to scroll to even see them), and which don’t require the customer to click a button saying they agree before accessing the website are called “browsewrap agreements” by the courts. But it is so easy to make these “browsewrap agreements” not an agreement at all, that we’re going to recommend that you never rely on this method of creating an agreement with your customers on your website.*

Courts do leave the door open for browsewrap terms of use to be enforceable. If they are conspicuous on the website, i.e., if TERMS OF USE was in all caps while “about us” was in smaller font, or if it was in the center of the page – the point is that it has to be large enough that a customer would see it and have notice that the Terms of Use will form a contract if the customer continues to access the site. (The court doesn’t state that the language of the terms have to be visible to the consumers, although that would probably be a safe way to go if you can give that much real estate on your home page). If there is evidence that your customers have notice of your Terms of Use and continue to access the site, then you have shown that they have accepted and agreed to your terms in exchange for the benefit of accessing the site. You have met the elements of a basic contract.

We could talk about font points and layout of the screen, but trying to guess how “conspicuous” your Terms of Use have to be for a court to find them enforceable is an unnecessarily dangerous game to play, in addition to being very likely to screw up the beauty of your user interface.

“Clickthrough” agreements, fortunately, take care of these elements nicely. Your users manifestly accept your offer and express their agreement to your Terms of Use by clicking on the button that says “I Agree.” Yes, we are fully aware that nobody ever actually reads the Terms of Use. But not reading a contract before agreeing to it is no defense (so be careful what you sign!)

The lesson here is pretty simple. If you want to be able to rely on contractual terms like an arbitration provision, or venue, or special disclaimers of warranty, or anything else that a customer would not otherwise have notice of, make your customers manifest their assent to those terms. You can do it by stamping the terms across the home page of the website if you want, but clickthrough agreements are probably cleaner.

There’s still more that was wrong with Zappos’ Terms of Use, but we’ll save that for next time.

* We do recommend clickthrough agreements when you need to create a contract, for example, if you want your customers to be subject to an arbitration provision, or if you want them to indemnify you if you get sued for their wrongdoing on your site. But we also recognize that clickthroughs can sometimes be awkward, with no good place to put them. For instance, we have not used a clickthrough on this website. Instead, our Terms of Use (which only provide information about our Copyright Policy and the limitations of the information we provide) our conspicuously set out in a tab at the top of our screen. Unfortunately, it isn’t always easy to tell whether what you want is to create a contract or simply provide information, and of course we aren’t giving legal advice in our blogs. But, dear readers, when you have these types of questions, that is what we are here for!