Parody ≠ Transformative Use

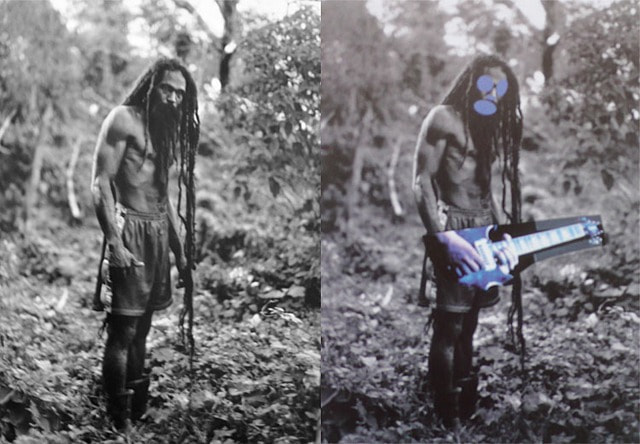

I know you’ve been playing Is it Fair Use? the fast-paced, brain-teasing game that’s sweeping the nation. That means you’ve already played the very first installment, which involved an “appropriation artist,” some photographs of Rastafarians, and a cancelled art show. If you haven’t, or you want to refresh your recollection, go play that round, then come back here. Meanwhile, here’s the main image I focused on in that case, Prince’s Graduation (right), and the Cariou photograph he borrowed:

Left: Patrick Cariou, Photograph from Yes Rasta, p. 118. Right: Richard Prince, Graduation

So it wasn’t fair use, right? And I said that the decision (read it again here) was about as well-reasoned as you’ll find? I thought the two most important facts were (1) that Cariou had an exhibition planned but it fell through when Cristiane Celle, the gallery owner, found out about Prince’s exhibition; and (2) that this, a work called Graduation, was a typical example of Prince’s “transformation” of Cariou’s work. I expressed concern, however, that the case seemed to turn on how well the artist was able to explain himself.

Is his Case More Appealing Than his “Art”?

Let’s play again, but at the appellate level, because, of course, Prince, the appropriation artist, appealed. The appellate court didn’t read the record quite the same way the district court did:

1. The district court left the fact that when Celle, the gallery owner, found out about Prince’s show, she called Cariou to ask him about it. When he didn’t respond, she concluded that Cariou had decided to ditch her little gallery in favor of the bigger gallery that the Prince show was at, on the mistaken assumption that Cariou must be involved with Prince’s show.* It was clear that she didn’t want to do a “Rasta” show at the same time as Prince was doing such a show, and she offered Cariou an opportunity to exhibit other works, but he didn’t follow up. In other words, she would have cancelled Cariou’s Rastafarian exhibition in favor of any “Rasta” show, not just an infringing one, and nothing prevented Cariou from have an exhibition, just not the Rastafarian one at that time.

* Her deposition testimony on this point is a little piteous: “[Maybe] he’s not pursuing me because he’s doing something better, bigger with this person [i.e., Prince]. … [H]e didn’t want to tell the French girl [i.e., Celle herself], ‘I’m not doing it with you, you know, because we had started a relation and that would have been bad.”

2. Prince’s works have a very different sensibility from Cariou’s. Prince’s works are ugly, “provocative” (whatever that means) and avant-garde. Carious, by contrast, is a skillful and highly naturalistic (in both senses of the word) photographer.*

* For whatever reason, Prince is magnitudes more popular than Cariou.

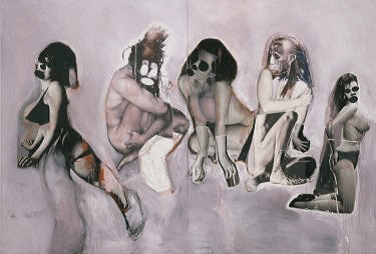

3. Of the 30 works at issue*, five were like Graduation, depicted above, where Prince merely took a full photograph and painted over it. In the other 25 works, he cut pieces out of the photographs and used them in ugly or shocking collages, like this:

Richard Prince, James Brown Disco Ball, a collage. The heads are from Cariou’s photographs. The bodies are from elsewhere. No, I don’t know why it’s called “James Brown Disco Ball.”

* Did you even know there were 30 works at issue from reading the district court opinion?

So: Reversal or Affirmation?

Before you answer, let’s consider something else—something I totally missed. While I thought the cancellation of the Cariou’s show was almost dispositive (i.e., it, without more, would defeat fair use), the district court’s main argument was that Prince’s works didn’t comment on Cariou’s work in any way. Prince’s works, therefore, were not “transformative,” and if they weren’t transformative, they really don’t stand much of a chance. Her main evidence was Prince’s own subjective testimony that he didn’t care about the works he was appropriating—just trying to use those works to create something else.

There’s something that doesn’t quite follow in that logic (and again, I missed it). The district court’s reasoning would be 100% correct if you replaced “transformative” with “parody.” That is absolutely the law of parody: the new work must comment (in some way) on the work from which it borrows. That’s important because, as we’ve discussed before, parody is a very powerful finding, It turns fair use on its head, so that facts that would work against fair use (such as amount and substantiality taken) actually work for fair use.

But parody and “transformative” aren’t the same thing. “Transformative” may be impossible to define, but it is certainly either a broader or different concept than parody. Most important: to be transformational, the new work need not comment on the work from which it borrows. We can complain all we want about whether “transformative use” is really all that helpful a concept, but it is surely wrong to import a rule limited to parody into the rules governing “transformative use.”

So, did the Second Circuit reverse or affirm the district court’s holding that there was no fair use? Find out here.