When American Exceptionalism Isn’t Exceptional

Americans assume copyright is something you have to register for. The rest of the world assumes either registration is voluntary or honestly doesn’t know what you’re talking about.

The truth about copyright registration, in the United States, is a little more complicated. Or, more accurately, a little more mystical. You do not need to register a work to have copyright in it. Copyright attaches itself (“vests in”) the author as soon as it’s “fixed in a tangible medium.” As a result, almost everything you’ve ever written, doodled, painted in an art class, sculpted out of Play-Doh®, sketched out, etc. is protected by copyright.1For the rest of your life, plus another 70 years, so your heirs can benefit from those notes, doodles, emails, finger-paintings, etc.

BUT: Unless and until you register your work, you cannot enforce the copyright.

Having an unregistered copyright is a bit like having only the blueprints for a house, then trying to live in it.

OK, it’s not that a big of a deal, right? If someone is infringing your copyright, you just apply to register the work, wait a several months for the registration to issue, then sue. If you can’t wait that long, you can pay an extra $800 for “special handling,” which speeds up the process considerably but isn’t always all that “special.”

This is all well and good, except for one thing. What if you screw up the copyright application and get a screwed up copyright registration? It’s really, really easy to screw up a copyright application. And the consequences can be brutal.

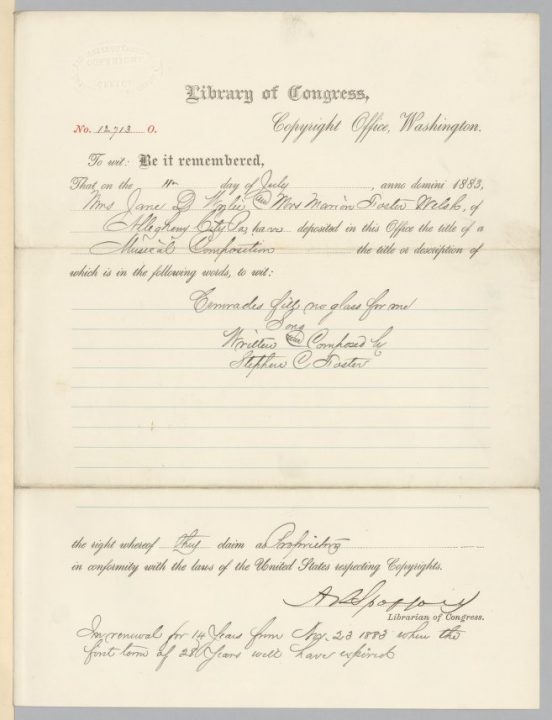

A Certificate of Copyright Registration from 1883 for a Stephen Foster Song. Such neat handwriting! Source: University of Pittsburgh.

Nine Bad Works Spoil the Unit of Publication

In Unicolors, Inc. v. H&M Hennes & Mauritz, L.P., the plaintiff, Unicolors, had combined a number of textile designs into a “unit of publication” registration. One of those requirements for this kind of registration is that the works comprising the “unit of publication” must be sold or offered for sale “in some integrated manner.” The unit of publication contained 31 designs, but nine of them were sold separately and shouldn’t have been included.

The H&M copied one of the designs, called EH101 (exciting name, I know). EH101 was not one of the separately-sold designs. The jury found the H&M’s infringement was willful and awarded Unicolors over $800,000 in damages, which was reduced to about $266,000 (not sure why). The court then awarded plaintiff over $500,000 in attorney’s fees.

H&M appealed, on grounds that the registration was invalid. The Ninth Circuit agreed and threw the entire jury award out, along with the award for attorney’s fees.

Keep in mind two things:

- The jury found H&M willfully infringed the EH101 design.2Important note: H&M attacked the jury verdict, too, but those issues weren’t touched on by the Ninth Circuit because it had already decided enough to have the case resolved on simpler grounds. If the jury verdict is reinstated, those issues for appeal would spring back to life. For all I know, they’re very powerful.

- The EH101 design was part of a legitimate “single unit of publication”; it’s just that nine of the 30 other designs weren’t.

Just a Dumb Mistake

Unicolors argued that, at worst, it just made a mistake by including the nine designs. As far as it knew, it was appropriate to include the nine designs. It thought the key was when the designs were first made (i.e., fixed in a tangible medium) and whether they were designed together. But “publication” is a term of art in copyright law, and it carries with it it a connotation of presentment to the public. In this way, we sometimes (mistakenly) think of a “publisher” as a manufacturer of books, when, really, it’s what puts books before the public. Lawyers get this. Non-lawyers, not always.

To be fair, had Unicolors’ folks read the U.S. Copyright Office’s circular on the subject, they would have read that they could:

…register a number of published works on one application with one filing fee provided that the works were physically packaged or bundled together as a single unit and that they were first published3There’s that word again. in that integrated unit. Such a registration is known as the “unit of publication” option.

All the same, the Ninth Circuit spends a solid two pages, and at least one “canon of construction” (noscitur a sociis), and one citation to Scalia & Garner on Interpretation of Legal Texts, plus a footnote making reference to Skidmore deference, to reach what it otherwise regards as a no-brainer interpretation of “unit of publication.”

But wasn’t this just a dumb mistake by Unicolors? The Ninth Circuit says it doesn’t care. All that’s required is that Unicolors knew that it was mixing in those nine designs into the same application. It doesn’t matter whether Unicolors understood this was a mistake.

Saving Fees, Losing Millions

The game isn’t quite over for the plaintiff, but I wouldn’t have high hopes. The case returns to the district court, with instructions to ask the U.S. Copyright Office to determine whether it would have refused registration had it known about the nine designs that were sold separately. I have to think the answer would be “yes.”

If that happens, then the lawsuit must be fought all over again. Presumably, plaintiff would win again, though (1) you never know, and (2) the award might be different. It will have zero hope for attorney’s fees, though, because the right to attorney’s fees depends on registering the work at issue before the infringement starts. Obviously, that horse has long left the barn. If it costs $500,000 to win $266,000, that’s not a good deal for the plaintiff.

All this to save a few bucks. Had plaintiff registered those nine stray designs separately, it would’ve cost just a few hundred dollars.

This is, to my mind, an obvious miscarriage of justice, and a waste of judicial and everyone else’s resources. If you take the jury verdict at its word4See footnote 2, supra., a larger and more powerful company—H&M—ripped off a smaller designer and will likely get away with it because the designer misunderstood some arcane legal stuff.

Surely There Are Better Remedies?

Why is throwing out the verdict a reasonable remedy for plaintiff’s mistake? It is the logical result, if not the equitable result, on the theory that the plaintiff never had a right to sue in the first place. And this can happen in other contexts, e.g., a jury finding that it lacks personal jurisdiction, or a court finding out it lacked subject-matter jurisdiction after judgment. But those go to constitutional rights.5Personal jurisdiction implicates the right to due process. Subject-matter jurisdiction goes to the general power of courts under Article III. The registration requirement just seems so, so ministerial. It’s too bad that the plaintiff can’t just pay the missing filing fees plus a penalty to the U.S. Copyright Office, and move along. But no: you can’t even fix a bad registration, just file for a separate supplementary registration that exists in tandem with the old, bad registration.

The Case Against (Quasi-)Required Registrations

Why do we even have copyright registrations? Hardly any other country requires them (practically speaking). I’ve heard a number of reasons. The main one is that it encourages authors to deposit copies of works into the Library of Congress. Technically, all publishers are supposed to deposit two good copies of every work with the U.S. Copyright Office, but not everyone does, so registration, which has its own deposit requirements, is a good backstop. This is a nice idea, but screwing over copyright owners doesn’t actually help. In the Unicolors case, the works were deposited. The main problem was the U.S. Copyright Office just didn’t get all the fees to which it was entitled.

Another reason is that it creates a running catalogue of all works. Which is also nice. But it also fails of its essential purpose, which is to identify current owners of copyrighted works. Further, it’s not easy to search for works that don’t have obvious titles (“EH101” anyone?).

Another reason I hear is that it acts as a brake against massive copyright litigation. People who don’t care enough about their works to register them don’t deserve things like statutory damages and recovery of attorney’s fees. Even so, there are better ways to achieve this goal that don’t involve screwing over copyright owners with honest grievances.

The rest of the world gets by without a quasi-mandatory registration system. Perhaps that’s the real reason: Americans just got to be different.

Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | For the rest of your life, plus another 70 years, so your heirs can benefit from those notes, doodles, emails, finger-paintings, etc. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Important note: H&M attacked the jury verdict, too, but those issues weren’t touched on by the Ninth Circuit because it had already decided enough to have the case resolved on simpler grounds. If the jury verdict is reinstated, those issues for appeal would spring back to life. For all I know, they’re very powerful. |

| ↑3 | There’s that word again. |

| ↑4 | See footnote 2, supra. |

| ↑5 | Personal jurisdiction implicates the right to due process. Subject-matter jurisdiction goes to the general power of courts under Article III. |